16 Jul Paesant traditions and silk

Article written by an enthousiast reader for the “Witnesses” series, dedicated to who, just like us, gives its daily contribution to spreading knowledge about this fiber, so natural and precious.

The first time that, when I was a young boy, I entered the refined palace overlooking the square of Ceneda’s Cathedral, once belonging to my great-great-grandfather who has been the first Mayor of Vittorio Veneto, I found myself highly surprised in finding how its internal courtyard and the huge surrounding fields gave it an unexpected rural appearance. Signs of peasant activities were still tangible in the dry-stone built warehouses and in the tiny red farmhouse that once was the cowshed.

On the inside of the palace, the owner’s floor was heated by one big cheminee and an old wooden stove. On the other hand, attics had many little cone-shaped cheminees. Why were they there? What was the aim of heating attics?

“To allow all the eggs to open on the same day, and for the newborn worms to be protected from excessive humidity and sudden temperature changes.” My father’s reply immediately brought me into a history unknown to me up to that moment: the wonderful world of silkworms, locally known as “cavalier”. A history that belonged to every citizen of Vittorio Veneto, since the entire population was deeply involved and committed to this productive sector. I then discovered how silk hanks left from my hometown, Vittorio Veneto, and reached Austria, the Balkans, Russia, but also Northern Europe and America.

It was clear how also my great-great-grandfather, as a serious Mayor, was ccommitted and wanted to give his personal contribution. He was among the few citizens so lucky to have attics with cheminees entirely devoted to taking care of worms (“cavalier”).

Most of paesant families, for whom silkworms’ sells constituted an important source of revenue, found themselves forced to breed silkworms in the same rooms where they lived, passing on narratives and stories of the tiny crucial eggs, named “seme bachi”, which were bred in bedrooms, protected under matresses or bedsheets.

Breeding silkworms was everything but an easy task, demanding the implication of each member of the family: from those who “booked” the little worms to be able to carry them home as soon as they were born, to those who were buying and taking care of the eggs, keeping them warm for the delicate period of time necessary for them to open up. Silkworms were bred with mulberry leaves for about 30 days, but attentions continued for 10 more days; in this period, the silkworm built up its shell, anchoring it to some tiny withered branch, perfectly dry, used to create the so-called “wood”.

During the second half of the 19th century, while our region was part of the Lombardo-Veneto reign, a devastating pandemic spread out through the whole European continent, hitting silkworms and reducing their production to zero. Silkworms breeding could recover only thanks to specifi institutions dedicated to overooking safety and soundness of the eggs and to silkworms breeding; only those certified as healthy could be used to produce cocoons.

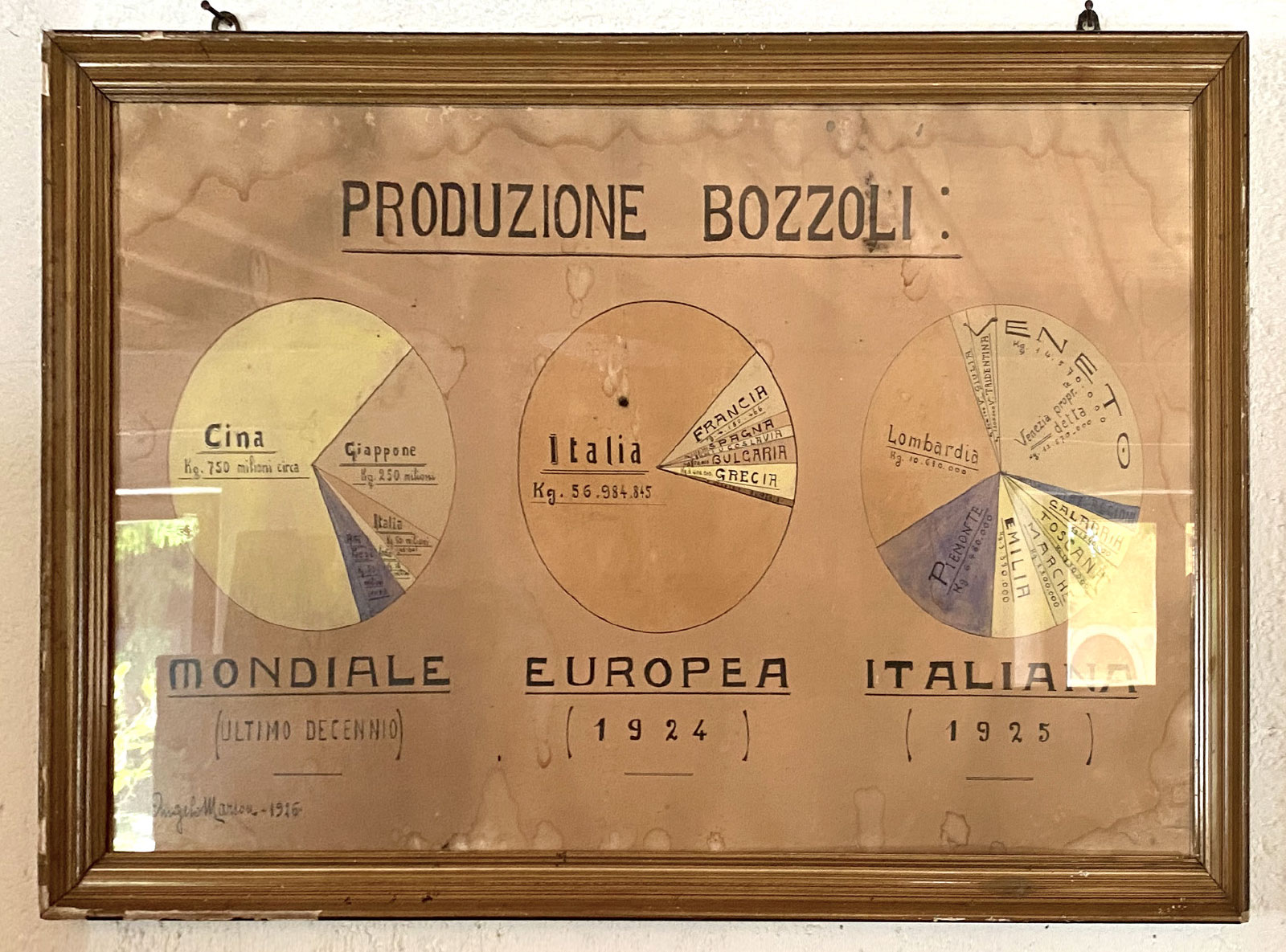

Vittorio Veneto city eccelled at this activity and soon became the second main cocoons production centre after Ascoli Piceno. Both hills and the upper plain witnessed a huge spread of sericulture, which helped overcoming a closed economy based on self-consumption.

Thanks to silkworm breeding and to the subsequent economic stabilty it could guarantee, typical countryside houses slowly became a family-based production centre. A socio-economic phenomenon that helped trnasforming both the life and culture of my hometown, but also those of many other villages all over our Country.

Silkworms’ breeding had a deep impact on our local communities, boosting the birth of labor, economic and organizational habits still to be found nowadays; not only that, but it also spurred team spirit, both inside families and within the community. The first forms of cooperation were born precisely in relation to silkworms’ cultivation. Worms’ life cycle, which tranformed itself into a chrysalis first and than into a butterfly while sleeping inside the cocoon, had a strict timetable which left no space for error; consequently, this meant the need to cooperate with each other. It was in this context that the so-called “incubation chambers” for the allocation of newborn cocoons to all the local farmers were created, as well as the “cocoon drying warehouses”.

Grazie al continuo sorgere di filande, nelle quali si ricavavano le mattasse di seta greggia, moltissime donne trovavano per la prima volta una realtà occupazionale al di fuori delle proprie mura domestiche.

Una vera rivoluzione insomma, intorno ad una fibra tessile che ha una storia plurimillenaria e che oggi affascina più di ieri.

Prooving the relevance of silkworms’ breeding in my area, we can find two wonderful museums in Vittorio Veneto.

The first is public, and can be found in the former Maffi Mill in San Giacomo di Veglia. This museum returns some traces of both personal and collective memories, as to show new generations the complex agricoltural, scientific and social environment that, for a very long time, revolved around the wonderful world of silkworms and its precious product: silk.

The second is private, and is located in the Marson’s “Osservatorio ed Istituto Bacologico”, in Meschio; this museum documents the history of the industrial field prior to silkworm eggs’ production which, between the ninteenth and the twentieth centuries, featured Vittorio Veneto for almost a century.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.